Although we’ve only had it 6 years, our Land Rover is now almost 20 years old. Apart from a few well documented repairs while we’ve been in Africa, it’s in what could (perhaps generously) be called ‘very original condition’.

All of the overland equipment was fitted before leaving the UK (fuel tanks, fridge, solar panel, rooftent, oil coolers, seats, security, etc) but various previously documented repairs on the road have ensured that we’ve marked our territory as we’ve travelled round Africa – usually with a large oily stain on the track somewhere.

In addition to a string of bush-welds, repairs and patches to the chassis and brakes, we’ve completely replaced the gearbox, rear cross member, clutch, rear axel and suspension.

A bit like Trigger’s broom (“I’ve had this same broom for 20 years: 17 new heads and 14 new handles in its time“) it’s in very original condition.

But all these repairs were really just minor inconveniences – although at the time a number of them were fairly buttock-clenching moments.

I guess the biggest problem has been the rust. Typical British car: used on salt-covered roads throughout winter.

I was told by a number of people before we left that the chassis was a bit ropey and probably wouldn’t make it. Unfortunately, one of those people was not the guy from Nene Overland who sold me the car when we told him we wanted a vehicle to fit out for an African trip.

No doubt it’s ultimately up to me to be sure that I’m aware of the condition of the car before buying it, but having spent over £17k on additional equipment with them I had hoped the basic car they sold me would be structurally up to the job. What do I know? The only thing I’m certain of regarding cars is my mechanical incompetence.

Anyway, I’m not bitter about the chunks of rust falling from the chassis; the tinkling of rust settling within the doors every time they’re slammed; the way the rear chassis snapped in the middle of nowhere in The Serengeti; the way the A-Frame sheared in the desert east of Lake Turkana (leaving the rear of the body lurching in the opposite direction to the chassis over every axel-twisting bump); the way the suspension collapsed in northern Namibia (now that really is remote); or the way the step pushed through the rear cross-member when I put my considerable weight on it after it had been fitted to rusty steel that had been filled and painted over.

Not bitter at all. All part of a learning experience.

Besides, every time we’ve been stranded somewhere, we’ve ended up meeting some fascinating, generous, welcoming and friendly people who’ve gotten us out of the deep do-do we found ourselves in.

However, when John from the Stitch & Sew workshop in Fort Portal was servicing the car he found some pretty serious holes in a number of places on the chassis. Something more radical than a bit of bush-welding would be needed if we were going to get through the rest of the trip in Africa and have any chance of the car being classed as roadworthy when we get home.

He said we should start by creating a bit more ‘engine room’. Fortunately he has a department specifically to do that…

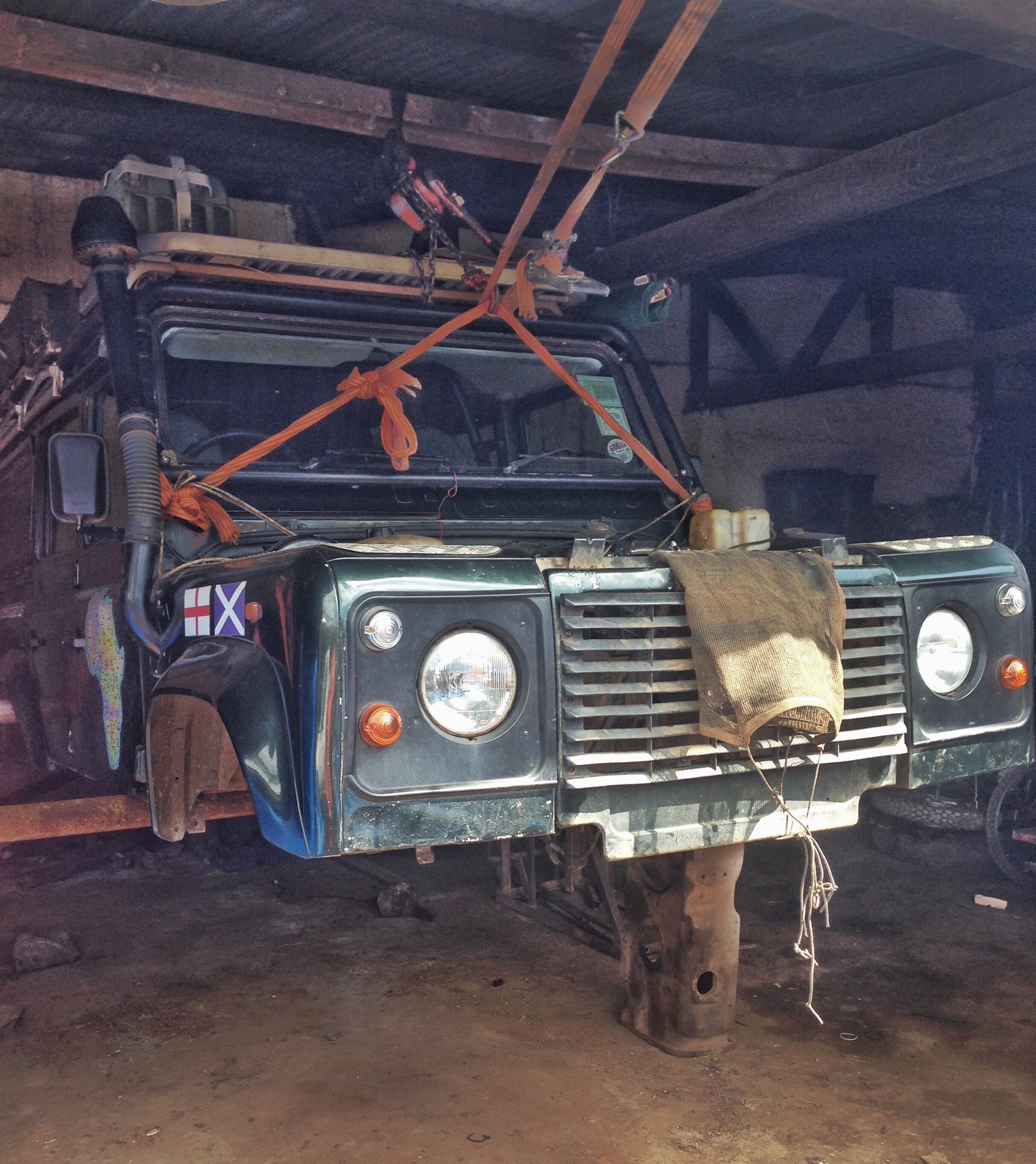

No, we hadn’t decided to just jack it up and enter it into some monster-truck races. The time had finally come for a chassis replacement. John and the Stitch & Sew team are the only guys in this part of the world I’d trust to do it. Equally importantly, he had a chassis from a ’98 Station Wagon, it was in good condition and his labour costs are 80% less than the guys back in the UK.

Unfortunately, although John is the main Toyota Service Centre for western Uganda, his hydraulic lifts won’t be delivered for another 8 weeks. Getting the body off would need to be done the old fashioned way.

A couple of farm-jacks, a few bits of timber and some steel poles. Even the mechanics seemed to be thinking “are you sure you want to watch this…?”

“…are you really sure..?”

John seemed calm enough. “Don’t worry Scott, we’ll have your donkey back on the track in 9 days.”

I don’t think Helene was convinced…

24 hours later, the cocoon was suspended from the roof of the workshop…

…and John was able to find a bit of shady peace from where he could work in peace…

I think there’s little doubt that the new chassis is in slightly better condition than the old one – despite it being exactly the same age.

Once the mechanicals were disconnected and rolled away, the really messy work could begin.

Once the mechanicals were disconnected and rolled away, the really messy work could begin.

Don’t you wish you’d patented WD40 – is there anywhere in the world where it’s not the most important tool in every mechanic’s kit?

We returned to Kasese and left them to it for a few days. By the time we got back everything had been reassembled and the underside of the car was sprayed with Rhino Paint (a thin Waxoil-style protective coating).

The whole team were very thorough. With so many bolt-on-bits (extra fuel tanks, side rails, tow-bar, differential & steering guards, water tanks, etc) there were hundreds of connections to be made and the final inspection took a couple of hours.

We’ve been back on the road for a week now and the car’s driving much better. It will go back to Stitch & Sew for a final check in a day or two – just to make sure nothing’s worked loose but first impressions are that they’ve done a great job.

We’ve been back on the road for a week now and the car’s driving much better. It will go back to Stitch & Sew for a final check in a day or two – just to make sure nothing’s worked loose but first impressions are that they’ve done a great job.

Total cost to replace the chassis (and replace the windscreen that has been badly split for the last 12 months) 5 million Ugandan shillings. That’s around £1,050 / $1,600. The parts alone would have cost double that at home – and the labour at least double again.

So, just like Trigger’s Broom our old car is in very original condition.

I guess at some point I’ll have to replace the rust-ridden, dented, scratched body parts as well. At the moment though every scratch, sun-scorched bit of paintwork, sand-blasted window and dent has a sentimental value and brings back memories of one escapade or another in Namibia, Botswana, Kenya etc.